Pilot Study Demonstrates Potential for PTSD Treatment Program for Veterans, First Responders

Retiring from the U.S. Army in 2016 left Lawrence resident Matt Hastings unmoored. Hastings, a former combat aviation brigade chief, had been someone with skills in demand: He was the only one who could fly certain missions, who had qualifications and experience other instructors needed.

Suddenly it was all over.

“Retirement was something that everybody looks for,” he said, “but it was not what I thought it would be."

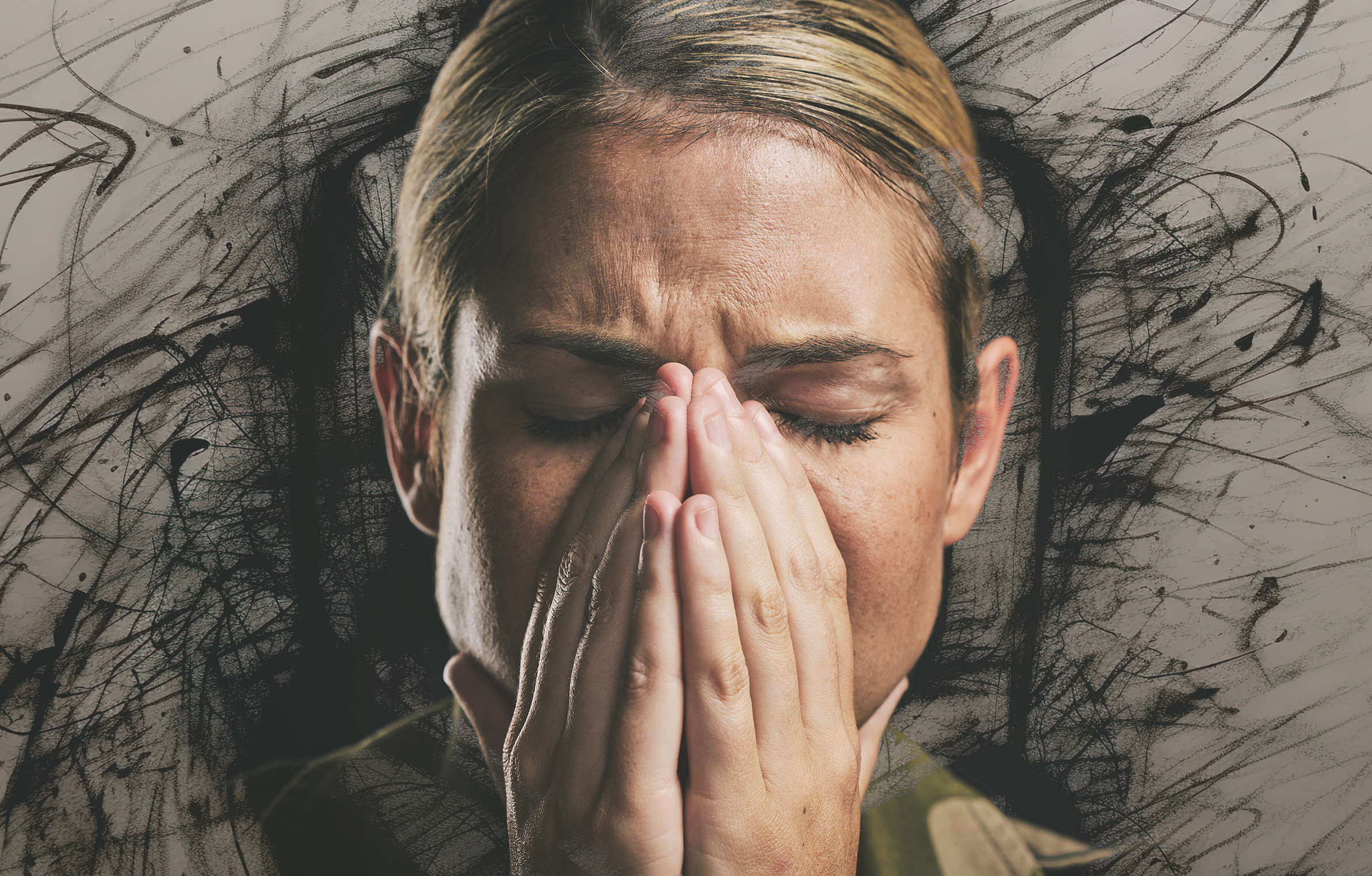

Instead, Hastings said he battled dark thoughts and kept punishing himself physically and mentally.

“I just was in that negative space,” he said. “And I just knew that — I didn't want to kill myself — but I just didn't see any other option.”

It wasn’t until Hastings was encouraged to try a program for veterans and first responders, developed with University of Kansas expertise, that he could address his emotional turmoil and post-traumatic stress. Now a recently published pilot study has shown how the program, called Warriors’ Ascent, can have a positive effect on veterans like Hastings.

In the pilot study, program participants had a substantially lower dropout rate (2.9%) than the average across all types of treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, treatment (36%). Treatment was found to be effective at reducing depression, post-traumatic stress and high-risk drinking. Many veterans struggle with the effects of PTSD, which leaves people feeling the continued effects of trauma even after the source of the danger or stressor is passed.

“First-line psychological treatments for these conditions are effective but can be lengthy and intensive, leading many veterans to drop out of treatment,” said Bruce Liese, clinical director at the Cofrin Logan Center for Addiction Research & Treatment at the KU Life Span Institute and lead author of the study, published in the Journal of Psychotherapy Integration.

The study surveyed 50 participants on the effectiveness of the brief, multicomponent group treatment offered by Warriors’ Ascent as an alternative to more lengthy interventions.

A 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, Warriors’ Ascent began collaborating with Liese after its founding in 2014. To date, nearly 600 veterans and first responders have gone through the program.

“We like to say that we empower our participants to take ownership of their lives and healing,” said Mike Kenny, executive director of Warriors’ Ascent, describing the organization’s approach.

The Warriors’ Ascent program involves a group retreat over five days. About a dozen participants engage in intensive interventions that include cognitive-behavioral education, mindfulness practice and emotion-focused practices at a retreat center in Kansas City, Mo.

Liese said the program also includes activities focused on nutrition, physical health, positive rituals and other activities for mental health and long-term life success.

The study noted that Warriors’ Ascent, with its brief, multimodal approach, may be a valuable resource for veterans suffering from multiple mental health problems, especially if they are not ready or able to participate in formal psychotherapy, or if they have tried psychotherapy and not found it to be helpful.

According to the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, about 10% of male veterans and 19% of female veterans had a diagnosis of PTSD in 2021. PTSD can contribute to mental health problems that increase the risk of mortality, including substance use disorder, depression, anxiety, eating disorders and suicidal thinking or actions.

Research has shown barriers to treatment of PTSD in veterans can include a perception that mental health care is ineffective. Barriers can also include financial concerns or logistical problems, such as distance from mental health resources. To manage these, participation in Warriors’ Ascent is brief, residential and free for veterans and first responders, Kenny said.

While less than half of the program participants reside outside of Kansas, travel costs may be covered by the program for eligible participants.

Kenny said that the program encourages participants to take care of themselves in a holistic way, which may conflict with the initial values of veterans and first responders as they enter the program.

"We (veterans) are a demographic, quite frankly, for whom self-care is anathema to the way we do business,” Kenny said. “The program in essence gives them license to take care of themselves. We say, ‘Self-care is not selfish.’”

Hastings, who is now on the organization’s board of directors, explained how he pulled into the Warriors Ascent parking lot doubting whether the program was right for him — whether he even had the right to be struggling as much as he had been.

“That was for other people who’d seen worse,” he said he thought at the time.

Still, Hastings didn't see other options. Sitting in his car, he debated whether to walk through the door. He realized he’d been hoping for a long time that things would change or ever get better.

"People that knew me before Warriors’ Ascent knew my mantra was, ‘Hope is not a plan,’” he said. “In the Army, you don’t hang plans on hope.”

Talking to Hastings, it’s now obvious that he does have hope – for himself and others who have participated in the program.