Study Reveals Less Connectivity Between Key Brain Regions in People with FXTAS Premutation

A new paper in the journal NeuroImage: Clinical from researchers at the University of Kansas reveals a possible early indicator of Fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome, or FXTAS. The disease afflicts some older people who carry a “premutation” of the gene known as FMR1, which can lead to impairments in movement and cognition — while other people who carry the premutation are unaffected.

Among people with the FMR1 premutation, scientists have struggled to find biomarkers to indicate who might develop FXTAS.

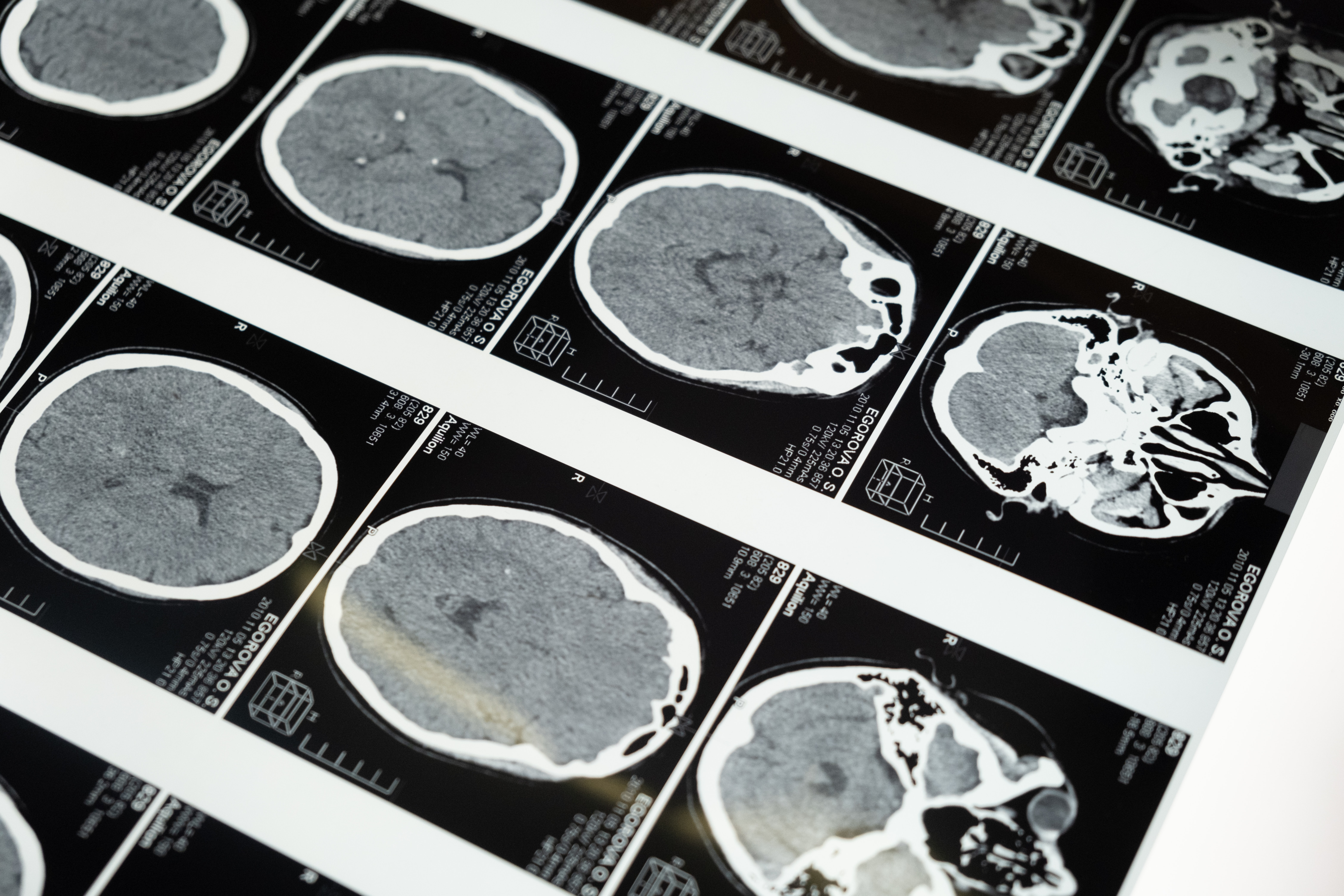

The new study of 16 people with the FMR1 premutation and 18 healthy controls recorded participants’ brain activity with functional magnetic resonance imaging while they performed a test of sensorimotor control. Participants were asked to manipulate images on a screen using a grip-force controller while the fMRI machine recorded the small changes in blood flow that occur when different parts of the brain become more active.

“It’s one of the first studies we know about to use fMRI to look at brain system function during motor behavior in a patient population at risk for developing motor deterioration and motor degeneration where they show a loss of balance, increased shaking or tremor as they reach their 50s, 60s or 70s,” said Matthew Mosconi, KU associate professor of clinical child psychology and associate scientist at KU’s Life Span Institute, who oversaw the investigation in his BRAIN Lab. “But we know very little about which premutation carriers will develop FXTAS. We know males are at greater risk than females. Otherwise, we don’t know a whole lot about which premutation carriers are going to get it. And we don’t know a whole lot about what’s going on in the brain functionally.”

The investigators were able to identify brain processes specifically linked to sensorimotor issues in aging people with the FMR1 premutation.

“We found the functional connectivity of cerebellum – a brain region that controls our movement accuracy and timing — and the extrastriate cortex, a brain area critically involved in processing visual information, is reduced in aging FMR1 premutation carriers,” said Walker McKinney, lead author of the new paper and a KU doctoral student in clinical child psychology. “In some people, these longer connections — like highways between the different parts of the brain — aren’t communicating as efficiently. Each part may be firing, but they’re not firing together.”

Significantly, the researchers found very little overlap in terms of functional connectivity of this pathway between premutation carriers and healthy controls in the study, suggesting connectivity levels between the cerebellum and extrastriate cortex could serve as an early emerging indicator of FXTAS, or predict who among FMR1 carriers will develop the characteristic symptoms of FXTAS before they develop.

“When studies get reported, oftentimes we’re talking about a ‘mean difference’ between groups — there’s always overlap with healthy people and there’s variability there,” Mosconi said. “With our study, the fact that there’s minimal overlap between premutation carriers and controls suggests that this may be what we would call a biomarker. What we need to do now is follow this measure and these people over time to determine who gets FXTAS and who doesn’t. In other words, this seems like a clear target for understanding brain degeneration in FXTAS and identifying it early in its course.”

McKinney and Mosconi’s co-authors on the paper were James Bartolotti of KU’s Life Span Institute, Dr. Pravin Khemani of the Swedish Neuroscience Institute, and Jun Yi Wang and Randi Hagerman of the University of California-Davis.

Other findings in the paper, which builds on the researchers’ previous investigations, include:

- Relative to healthy controls, premutation carriers showed increased trial-to-trial variability of force output, though this was specific to younger premutation carriers.

- Relative to healthy controls, premutation carriers also showed reduced extrastriate activation during force relative to rest.

- Increased reaction time was associated with more severe clinically rated neurological abnormalities.

- The work was supported by the Once Upon A Time Foundation and the Kansas Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (KIDDRC). A KU GO award is enabling followup research on these findings and biomarkers.